Chapter 7 Counterintuitive Applications

7.1 Birthday Paradox

How many people are needed in a classroom so that the probability of them sharing a birthday is at least \(\frac{1}{2}\)? Intuitively, one could claim that 183 people in the group would imply that the probability is greater than \(\frac{1}{2}\), since \(\frac{183}{365} = 0.501\). However, intuition does not correctly solve this problem.

To begin, there are some assumptions that need to be made. For simplicity, we will ignore leap years and assume that all 365 birthdays have an equal probability of occurring.

We want to compute \(P(\beta)\), the probability that at least 2 people share the same birthday. Recall from the previous chapter that \(P(\beta) = 1 - P(\beta')\). In this case, it is much simpler to calculate the probability that no one in the group shares the same birthday with someone else.

Let’s start with the simple example involving only two people. The probability that they do not share the same birthday is \[P(\beta') = \left( \frac{365}{365} \right) \left( \frac{364}{365} \right) = 0.997\] \[1 - P(\beta') = 0.003\]

Extending this result to a group of five people: \[P(\beta') = \left( \frac{365}{365} \right) \left( \frac{364}{365} \right) \left( \frac{363}{365} \right) \left( \frac{362}{365} \right) \left( \frac{361}{365} \right)\] \[ = \frac{365!}{365^5(365 - 5)!} = 0.973\] \[1 - P(\beta') = 0.027\]

This formula can be applied to any number of group size, so that in the general case of \(n\) people, the probability that at least two share the same birthday is \[P(\beta) = 1 - \frac{365!}{365^n(365 - n)!}\]

Finally, to solve the original question: how many people are needed in a classroom so that the probability of them sharing a birthday is at least \(\frac{1}{2}\)? Iteratively increasing the group size from five, it is clear to see that at a group size of 23, \(P(\beta) > \frac{1}{2}\) \[P(\beta) = 1 - P(\beta') = 1 - \frac{365!}{365^{23}(365 - 23)!} = 0.507\]

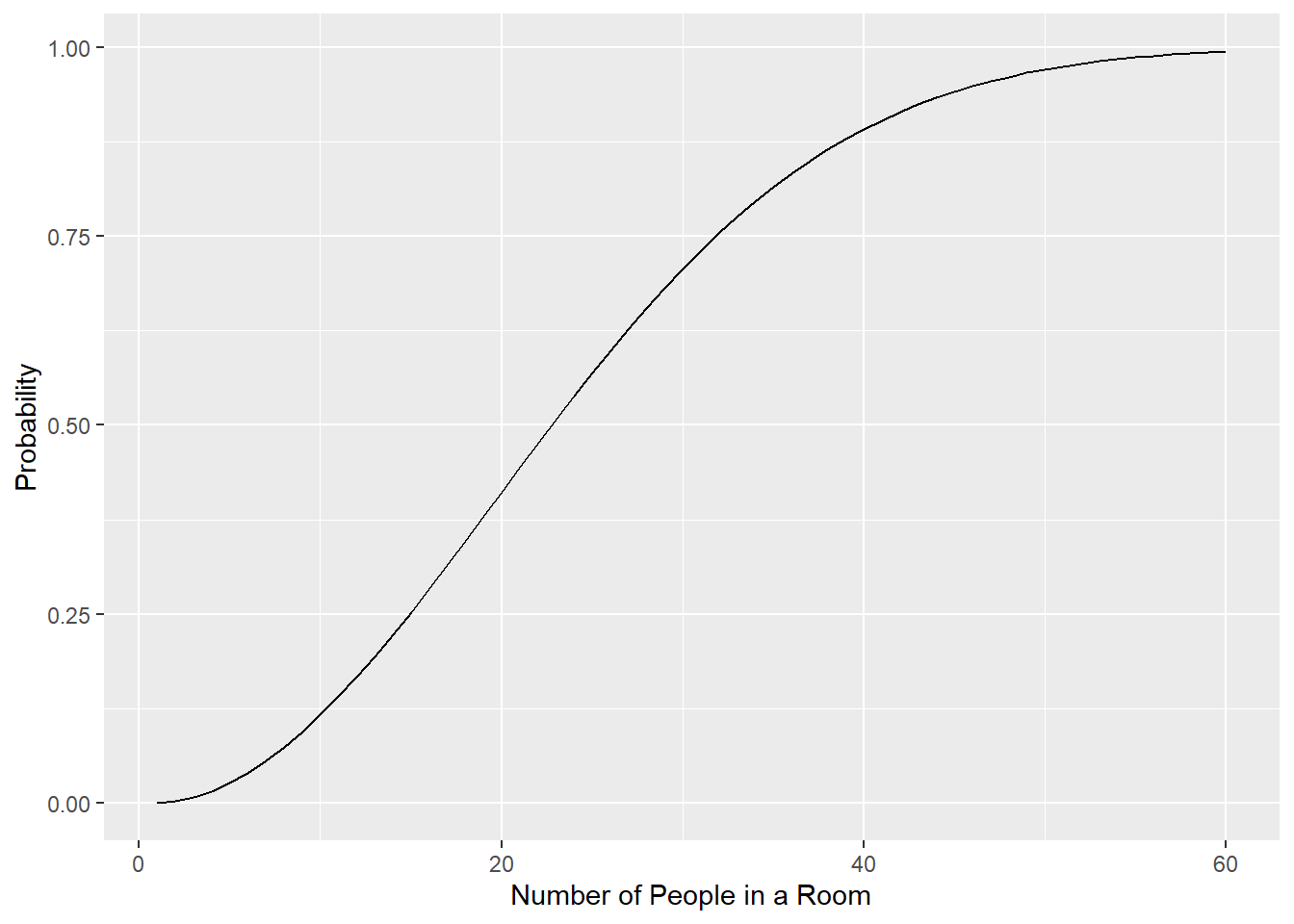

Figure 7.1: Probability of Sharing the Same Birthday

Figure 7.1 shows the probability increasing while the number of people in a room increases from one to sixty. Notice with only 60 people in a room, the probability of at least two people sharing a birthday is almost one!

7.2 Monty Hall Problem

The original problem was popularized as a letter by Craig F. Whitaker sent to Marilyn vos Savant’s column in Parade magazine in 1990.3

Suppose you’re on a game show, and you’re given the choice of three doors. Behind one door is a car, behind the others, goats. You pick a door, say #1, and the host, who knows what’s behind the doors, opens another door, say #3, which has a goat. He says to you, “Do you want to pick door #2?” Is it to your advantage to switch your choice of doors?

You can read more about the article here: https://web.archive.org/web/20130121183432/http://marilynvossavant.com/game-show-problem/↩︎